What to Know About The Cancer Train of Punjab

Inside Punjab’s ‘Cancer Train’: How the Green Revolution’s Dark Legacy Still Haunts Rural India

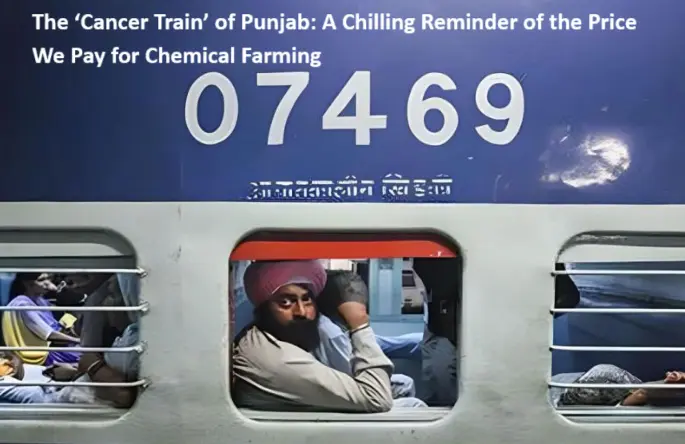

Every night at precisely 9:30 PM, from the dusty railway station of Bathinda—a farming town once hailed as Punjab’s agricultural pride—Train No. 339 departs. But this train doesn’t carry weary office workers or students heading home. It carries something far more tragic: cancer patients, mostly poor farmers and their families, bound for the government cancer hospital in Bikaner, Rajasthan.

Locals don’t call it by its number.

They call it “The Cancer Train.”

It’s a name that sends shivers down the spine. Not because of superstition or myth, but because of the haunting truth it represents—an epidemic of cancer silently swallowing rural Punjab. Every night, this train carries around 60 cancer patients, their faces tired, their spirits clinging to hope, in search of affordable treatment hundreds of kilometers away from home.

The Green Revolution: Boon or a Time Bomb?

In the 1960s and ’70s, Punjab led India’s Green Revolution. The once famine-stricken land was transformed through high-yield crops, chemical fertilizers, and pesticides. India became food-secure. Punjab was crowned the granary of India.

But fast-forward to today, and that very revolution seems to have sown the seeds of suffering.

Recent reports from India’s top medical and scientific institutions indicate that cancer incidence in high pesticide-use villages is significantly higher than in areas with less chemical exposure.

A 2013 study by Punjab’s Department of Health and Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh, confirmed that certain pockets of Punjab have cancer rates far above the national average, especially in Malwa region—where Bathinda lies.

The same region saw the heaviest pesticide use in the country.

Coincidence? Or cause?

Researchers cautiously clarify: “Correlation is not causation.” But when a single train becomes a lifeline for the diseased, the question becomes too urgent to ignore.

Poisoned Fields, Poisoned People?

Farmers in these regions routinely use banned or excessively toxic pesticides such as Endosulfan and Phosphamidon—many of which are outlawed in Europe and the US.

In Bathinda, residues of these chemicals have been found in groundwater, blood samples, and even breast milk.

A 2005 study by Greenpeace India found dangerous pesticide residues in food samples from Punjab, further fueling fears that the entire food chain may be contaminated—from soil to stomach.

While modern agriculture brought prosperity, it also brought a deadly side effect—a slow and invisible poisoning of generations.

Cancer on the Tracks: A Human Crisis

The Cancer Train isn’t just a symbol. It’s a daily heartbreak.

Most of the patients onboard are marginal farmers, often having sold land, cattle, or jewelry to pay for chemotherapy sessions. Bikaner’s Acharya Tulsi Regional Cancer Institute, a government-run facility, is their last hope. It offers treatment that’s affordable or free, unlike private hospitals that remain out of reach.

Families board the train with homemade rotis, blankets, and sometimes oxygen cylinders. They’ve made peace with sleeping on steel benches, washing up in station bathrooms, and queuing for hours.

They’re not just fighting cancer.

They’re fighting poverty, pollution, and a system that overlooked their suffering for decades.

A Wake-Up Call for the Rest of India

What’s happening in Punjab is not an isolated tragedy. It’s a cautionary tale.

Karnataka, Maharashtra, and parts of Andhra Pradesh are now increasing chemical inputs in agriculture, with similar patterns of pesticide overuse and unregulated sales.

If we don’t act now, the next “cancer train” could leave from another state.

The Case for Pesticide-Free Farming

The solution isn’t simple, but it's possible.

Organizations like Navdanya, led by Dr. Vandana Shiva, are promoting organic and regenerative farming that restores soil health and eliminates chemical dependency.

States like Sikkim have already gone 100% organic—and report fewer health issues, better biodiversity, and even higher farmer incomes due to premium organic pricing.

The Price of Progress

We often talk about agricultural heroes and food security. But we rarely talk about the hidden costs — the children who never made it to school because of cancer, the mothers who sell their mangalsutras for medicine, and the fathers who inhale death in the name of better yield.

The Cancer Train should not just carry patients—it should carry a message for policymakers, consumers, and farmers alike:

"We need to grow food that doesn’t kill the hands that harvest it."

Sources & References:

- PGIMER Chandigarh Study on Cancer Prevalence, 2023

Greenpeace India: “Chemical Harvest” Report